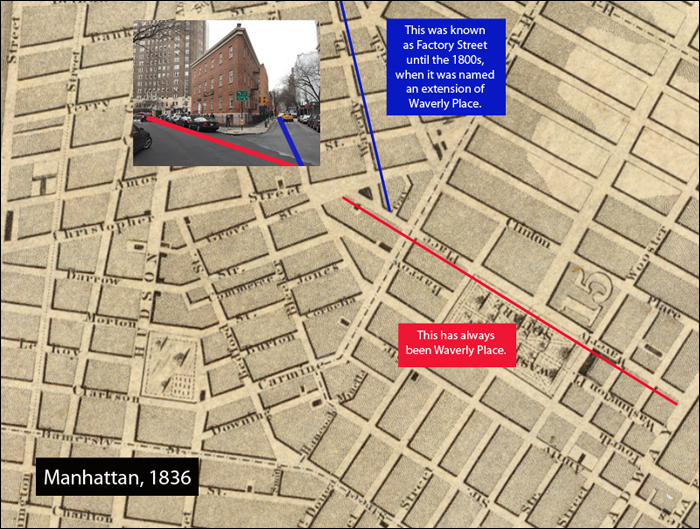

The Northern Dispensary:

Greenwich Village's Free Clinic

Photo © Peter McKie.

The Northern Dispensary was built in Greenwich Village in 1831 in what was then the northernmost part of New York City (hence the clinic’s name). The city donated a triangular plot of land for the clinic with the stipulation that it provide care for the “worthy poor,” a growing population in the Village.

The Village's Changing Face

Photo © Peter McKie.

Through most of the 1700s, Greenwich Village was a rural outpost of fields and farms. But as the population of lower Manhattan grew, so, too, did that of the Village, spurred in part by residents fleeing the epidemic diseases of lower Manhattan, including yellow fever. As the well-off built townhouses, tradespeople moved in, many of whom couldn’t afford medical care.

The clinics were funded by grants from the state legislature, by city funds, and through donations.

"Minutes, April 6th, 1827. At a meeting of Citizens held at the Rooms of Major Flint S. Kidder, April 6th, 1827, convened for the purpose of taking into consideration the expediency of establishing a Dispensary in the Northern section of the City, and taking measures to carry into effect the same, Alderman Peters was called to the Chair. Some proceedings relative to a former Association for similar purposes were read. Resolved that we proceed to the business of the present Meeting without any regard to the proceedings of the former Society. Mr. Floyd Smith proposed a Draft for a Constitution which was discussed by [indecipherable] and, after being amended was adopted as follows. The meeting then proceeded to the choice of Officers."

Photo © Peter McKie.

In addition to healing the poor, the clinics gave doctors the chance to study "distinct classes of disease," according to the New York Directory of Social Agencies.

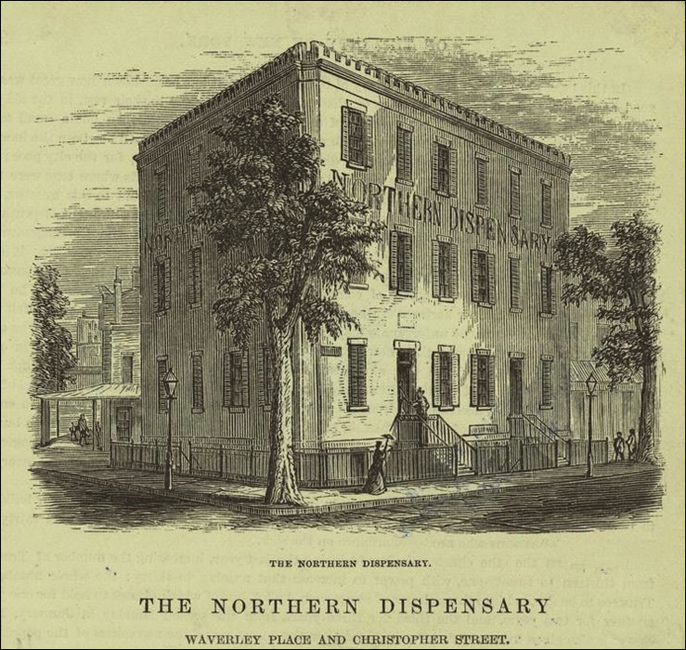

Initially, the dispensary operated out of temporary facilities at various locations. But in 1831, Henry Bayard, a carpenter, and John Tucker, a mason, built the dispensary's permanent home for $4,700.

The Dispensary Through the Years

Engraving © New York Public Library.

Coloured wood engraving © N. Orr & Co.

Photo © New York Public Library.

Photo © Library of Congress.

Photo © Library of Congress.

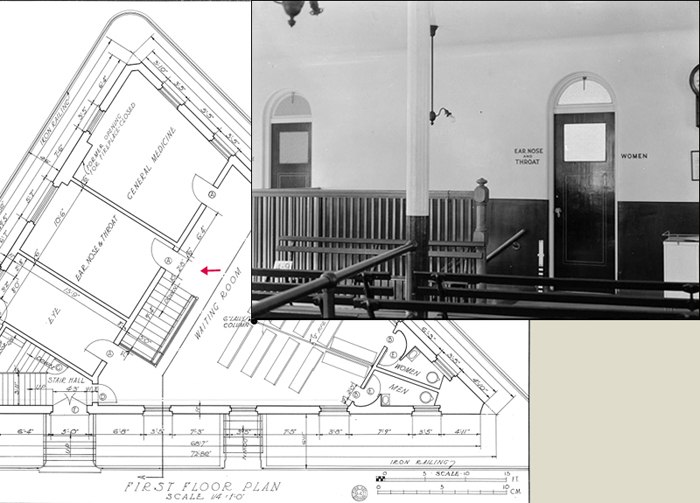

Drawing © HABS; photo © Library of Congress.

Map © J.H. Colton.

Photo © Peter McKie.

The dispensary cared for the city’s poor and sick primarily as inpatients until 1920, when outpatients outnumbered inpatients.

By the early 1940s, the clinic’s services were about equally split between medical and dental care. By the early 1960s, it provided outpatient dental care only.

Photo © Peter McKie.

Photo © New York Post.

While that meant that some of his buildings became shabby with neglect, warehousing had a positive side, too. Andrew Berman, executive director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, told the New York Post, “Without a doubt, had it not been for Bill Gottlieb, there’s a lot of buildings in the West Village and Meatpacking District that would have been torn down and replaced with sort of very generic and forgettable new construction, but instead kind of lived to face another day.”

Gottleib continued his habit of warehousing with the dispensary, which has been vacant since 1999. In the fall of 2016, however, the Dispensary's windows were covered in paper (see first image) and workmen could be heard inside, though whether they were simply maintaining the building to comply with building codes or renovating it is unknown.