The Keller Hotel

Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Photo © Detroit Publishing Co.

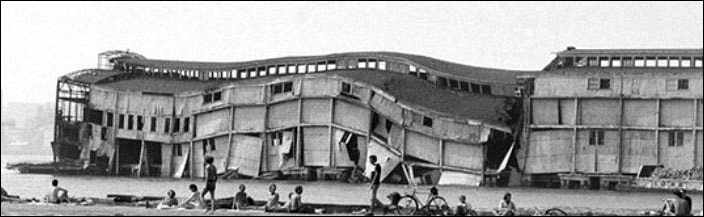

The Keller was built across the street from the Hudson River piers, then the bustling center of maritime trade in New York. From the late 1800s to the early 1900s, cargo ships, transatlantic cruise lines, and ferries all docked along the lower Hudson, disembarking thousands of seamen and travelers.

The Keller was one of many riverfront hotels built to cater to this trade. But in the early decades of the 20th century, freighters began to give way to container ships and cruise ships to air travel, and the waterfront went into decline. In 1939, the Federal Writer's Project's New York City Guide described the riverfront this way:

"Opposite the piers, along the entire length of the highway, nearly every block houses its quota of cheap lunchrooms, tawdry saloons, and waterfront haberdasheries catering to the thousands of polyglot seamen who haunt the front."

As commerce along the Hudson dwindled, the hotel had to adapt to survive. By 1935, the Keller was formally registered with the city as a home for itinerant seaman, a requirement designed to ensure safe housing in the run-down district.

Photo © Paul Hosefros/The New York Times.

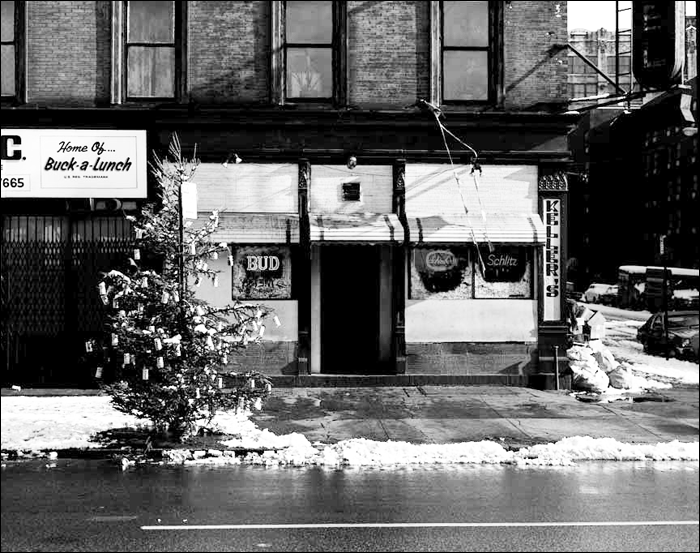

In the 1980s, as even river workers became scarce and the Hudson River piers were abandoned, the Keller became a single-room occupancy hotel (SRO), where people of little means could rent small, flimsy-walled rooms by the month. Still later, the Keller became a welfare hotel, where the city housed people on public assistance until it could find them permanent housing.

Today, the Keller is one of the last remaining turn-of-the-century waterfront hotels. That distinction, along with the stature of its architect, Julius Munckwitz (see below), contributed to the Keller's designation as a New York City landmark in 2007.

How the Keller Came to Be

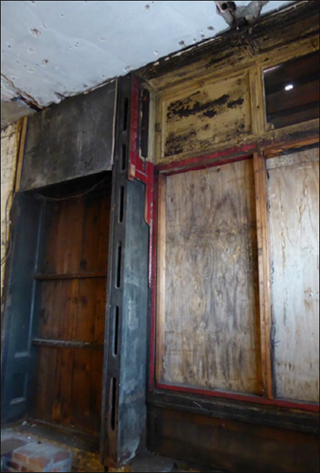

Photo © Morris Adjmi Architects.

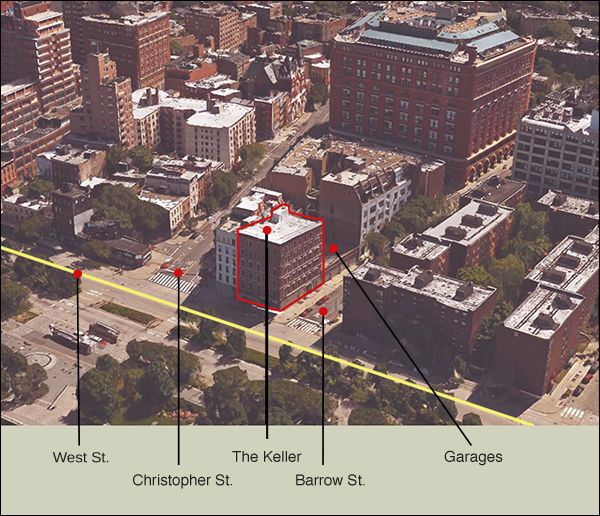

In 1890, Farrell bought all four lots, along with an adjacent one at 385 West St. In 1898, he built the Keller for $68,000 on the two West St. lots. He continued to use the other three lots, behind the hotel, for his coal business. Today, those lots house four single-story garages.

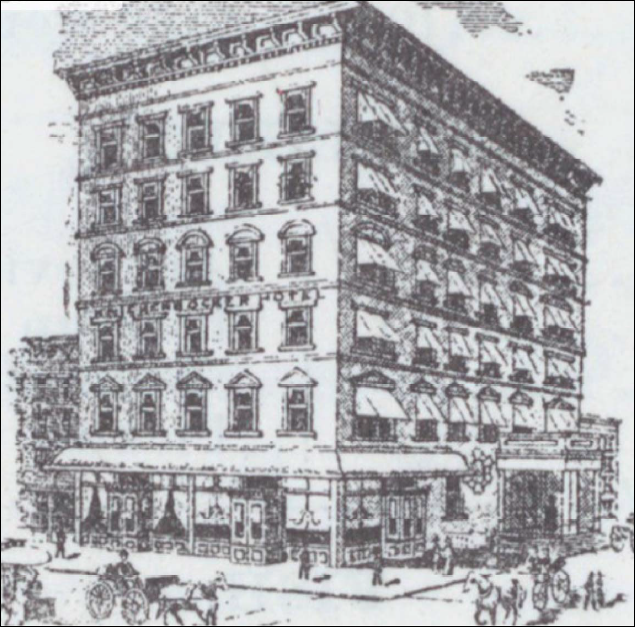

The Keller is a six-story Renaissance Revival hotel. The first floor of the Hudson-facing side of the hotel housed two storefronts that attracted West St.'s busy foot traffic, while the entrance to the hotel itself was around the corner, on Barrow St.

The Keller went through a number of name changes over the years. When it was first built, it was known as the Knickerbocker Hotel. In 1911, it was renamed the New Hotel Keller, and in 1929, it was the Keller Abingdon Hotel. From 1993 on, it was called the Keller Hotel.

Photo © Allan Tannenbaum

The Keller Through the Years

Photo © New York Public Library.

Photo © New York Public Library.

Photo © New York Public Library.

Photo © New York Public Library.

Photo © John Barrington Bayley, Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Photo © Peter McKie.

Photo © Peter McKie.

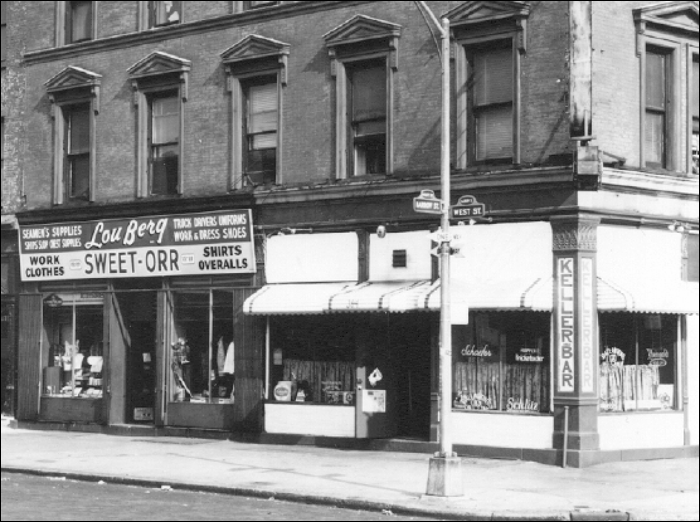

The Stores Over Time

While the Keller is built of brick, the two storefronts are clad in cast iron, which could support large plate glass display windows. The left-hand store, at 385 West St., housed many types of business over the years. They included a billiards parlor (John Dees, 1940), the Bering Marine Service field office (1945), an electrical engineer’s office (Jerome Jawitz, 1950), the Eastern Tire and Supply Co. (1953-1958), Lou Berg’s Seamen Supplies and Work Clothes (1959-1970), and a catering service called QQFS (1973-1975).The store on the right has been a restaurant or bar since at least 1939. It was the Renee Tavern from 1939 to 1949, the Charles Bar & Grill from 1950 to 1955, and the Keller Bar from 1956 until the hotel’s closing in 1998. The Keller Bar has its own fascinating history (see below).

Photo © New York Public Library.

Photo © New York Public Library.

Photo © New York Public Library.

By chance, the Keller was photographed twice in 1940, once as seen in this "tax photo" (where every building in the city was photographed by the city's Dept. of Finance), and once as seen in the carousel above.

Photo © New York Department of Finance.

Photo © Hank O'Neal.

Photo © New York Department of Finance.

The Keller Bar

Photo © Joseph.

Here's one customer's rememberance of the Keller from 1974, via a blog post:

"As we turned the corner onto West Street, I saw a few motorcycles parked in front of a small bar. A bright rosy light cast itself across the pavement from the two windows, illuminating the chrome detailing on the bikes. The red neon sign, hanging above, threw the now-silent trucks parked under the highway into stark relief. We opened the door and walked in.

It was a small, rather plain room, shaped like a shoebox. A door, with a window on each side. A rough wooden bar that ran the length of the room on the left. A pool table and jukebox on the right. A few strings of Christmas lights and dozens of handsome men crammed inside. The jukebox featured a mix of current soul and rock, along with the Ronettes singing "Walking In The Rain" and the Shirelles essaying "Chains". Later "Shame, Shame, Shame" would play incessantly, as the patrons danced in place, and the bartender hollered in faux-annoyance."Just as there are few remaining interior shots of the hotel, so there are few of the bar.

Renering © Morris Adjmi Architects.

Renering © Morris Adjmi Architects.

The Architect

Julius F. Munckwitz emigrated from Germany in 1849, when he was 20 years old. He ran his own architectural firm in New York, where he designed commercial buildings, hotels, office buildings, and apartment buildings. In 1857, he also began working for the city's Parks Department, and in 1871 he became the Supervising Architect and Superintendent of Parks.The Keller is the only one of Munckwitz's buildings still in existence, which partially accounts for the hotel's designation as a landmark. Munckwitz's other buildings have been demolished for new construction, though he is listed as a co-designer on three Parks projects that still stand: the Central Park Boathouse and Riverside Park, both in Manhattan, and a retaining wall in Morningside Park, Queens.

Munckwitz resigned from the Parks Department in 1885, but continued working as an independent architect until his death in 1902.

The Keller Becomes a Landmark

In 2007, New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) gave the Keller landmark protection, meaning that the building’s exterior cannot be altered without going through a rigorous approval process.The LPC cited two unique characteristics in designating the hotel a landmark: It is one of the last surviving turn-of-the-century riverfront hotels in the City, and therefore "a significant reminder of the era when the Port of New York was one of the world’s busiest and the section of the Hudson River between Christopher and 23rd Streets was the heart of the busiest section of the Port of New York." In addition, it is the only remaining example of Julius Munckwitz's work.

The Keller’s Future

Renering © Morris Adjmi Architects.

Photo © Peter McKie.

Renering © Morris Adjmi Architects.