The Real "Goodbar" Murder

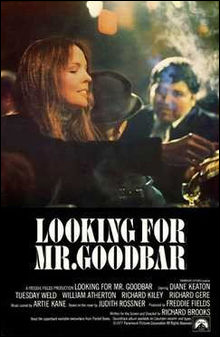

Photo © Paramount Pictures.

In the 1977 film “Looking for Mr. Goodbar,” Theresa Dunn is “a young woman living in New York City [who] leads something of a double life: by day she’s a devoted schoolteacher, but by night she cruises singles bars” (IMDB). The movie was a cautionary tale for single women coming of age in the Swinging 70s, when recreational sex was no longer taboo, or for men only.

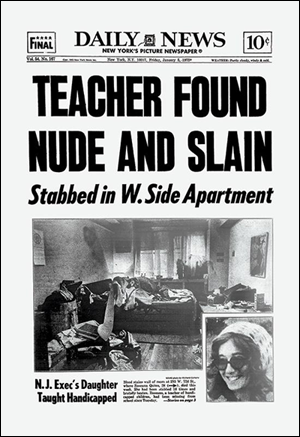

Photo © New York Post.

“Goodbar” is based on one of New York City’s most notorious murders, that of 28-year-old Roseann Quinn. Quinn taught hearing-impaired kids at St. Joseph’s School for Deaf Children in the Bronx. She was a single woman living on New York's still-sketchy Upper West Side. Shy and bookish by nature, she’d spend many nights in the corner of a local bar, sipping wine and reading books. Other times, she was more social, talking with regulars and sometimes inviting men back to her apartment. Neighbors said those assignations weren't always quiet, and some speculated that she liked "rough sex."

Photo © Newsweek.

Photo © New York Daily News.

Quinn grew up in a conservative, religious home in suburban New Jersey. She moved to the Bronx in New York in 1966, and to a studio apartment at 253 West 72nd St. in 1972. She spent a lot of her spare time outside her cramped quarters, usually at neighborhood bars.

On Monday, January 1st, 1973, no one could get her on the phone, nor did she show up for work for the next two days, out of character for the responsible teacher.

Her colleagues at St. Joseph’s became worried. On Wednesday, January 3rd, the principal sent a teacher to Quinn’s apartment. He knocked on the door, but got no response. After asking the building’s superintendent to unlock the door, they found Quinn’s body lying across her fold-out bed. She had been stabbed 18 times, 6 in the neck and 12 in the stomach. A red candle had been thrust into her vagina, and a statue lay across her face. A blue bathrobe, which had to be placed there by the killer, covered her body.

Photo © New York Daily News.

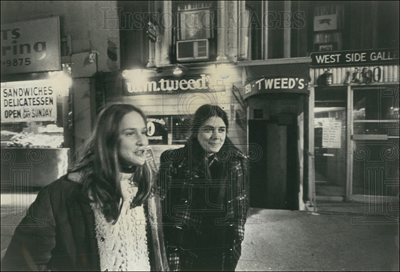

The cops had little to work with. They found no fingerprints in the apartment or elevator, and building residents said they didn't see or hear anything unusual. DNA analysis was decades away. That left the cops canvassing the neighborhood. One stop was the Copper Hatch, a bar next to Quinn’s building. The staff said that Quinn was a regular there, coming in two or more nights a week. They said she came in early on the morning of Tuesday, January 2nd, with several people from a bar across the street, W.M. Tweed’s.

Photo © The New York Times.

Over at Tweed's the bar's owner, Steve Resnick, said that Quinn was well-known there, too. In fact, he and Quinn had become friends over the 7 years he’d known her. Resnick said that Quinn always carried a book with her, and sometimes she’d order a glass of wine and read in a corner. Other nights, she'd order a Johnny Walker Red and mingle with other patrons.

Resnick said that Quinn had come into the bar at 9 or 10 the night of January 1st, and left with a group of people about 1 a.m. to go to the Copper Hatch. He also said that, despite Tweed’s being full of its usual customers, “there was one guy I didn’t know.” Resnick said that he saw Quinn talking to the stranger at the bar, and suggested the cops talk to the bartender.

Photo © Lauren Klain Carton.

The bartender reported that there were actually two unfamiliar guys in the bar that night, “nice guys, normal. Regular. Quiet,” he said. One of them left soon after the pair arrived. The other told the bartender that his name was Charlie Smith, and that he was in New York from Chicago, looking for work. When the cops asked the bartender to describe Smith, he said he was blond, big, and good-looking.

The police interviewed another Tweed regular who got into conversation with Smith, a barfly who earned money drawing caricatures. He said that Smith had an accent, “like out west,” and that he drew two pictures for Smith, one of Mickey Mouse, the other of Donald Duck. That was the break the cops had been looking for—both drawings had been found in Quinn’s apartment. Either Smith had given the drawings to Quinn, or he’d been in her apartment and left them there. Either way, the two had gotten to know each other during the course of the night.

Photo © The New York Daily News.

Over time, the cops would learn that the two strangers were Geary Guest and John Wayne Wilson, a.k.a. Charlie Smith. Guest was a gay 42-year-old executive in charge of finance at an advertising agency, and Wilson was a 23-year-old drifter and hustler from Illinois, in New York to escape a minor rap in Florida. The two men met in 1970 in Times Square, where they cruised each other, had a drink, and then headed to Guest’s apartment on 69th St., three blocks south of Tweed’s. By the time of Quinn’s murder three years later, their relationship had morphed into one of simple friendship.

The night of the murder, Guest and Wilson ate dinner a few blocks from Tweed’s and, as they passed the bar on the way home, decided to go in for a drink. Not long after, Guest grew bored and left, while Wilson stayed behind.

Photo © Google Street View.

As Wilson later told Guest, they smoked some weed, made out, and started having sex. But Wilson was too drunk to perform, and Quinn insulted him. Wilson became enraged and killed her.

Afterward, he took a shower, put his clothes back on, and wiped the apartment down using Quinn’s white nylon slip. He even wiped down the elevator as he left the building.

Wilson then went to Guest’s apartment and told him what happened, Guest was shocked, but didn’t call the police, and Wilson went to bed. The next afternoon, Guest gave Wilson money to leave town. Over the next few days, Guest and Wilson kept in touch by phone. Wilson’s first stop was Miami, to see his pregnant wife, and then he flew to his brother’s house in Springfield, IL.

Photo © New York Times.

Meanwhile, the cops couldn’t get a bead on “Charlie Smith.” In desperation, they released a sketch to the newspapers that appeared on Sunday, January 6th, four days after the murder. Guest saw the sketch and started to worry that it resembled him and that he might be implicated in the murder. He called his lawyer and told him everything. The lawyer advised Guest to go to the authorities.

Photo © New York Daily News.

The next day, Guest's lawyer cut a deal for immunity with the Manhattan Assistant District Attorney. Later that day, Guest met with the case detectives to tell them what he knew. Afterward, the detectives tapped Guest’s phone. The next time Wilson called, Guest got him to confirm that he was at his brother’s house. The following morning, detectives knocked on the brother’s door. Wilson looked up from the couch and said, simply, “Let me put on my shoes.”

The detectives flew Wilson back to NY to face charges. On May 5th, while being held for trial, Wilson hung himself in his cell using bed sheets.